This blog post is written by R. Joseph Rodriguez, former Chair, NCTE College Section.

In the famous poem titled “Poetry,” Marianne Moore declares, “I, too, dislike it: there are things that are important beyond all this fiddle” (28). What at first seems like an attack on poetry through a poem soon becomes a defense of it. Published in 1925, the poem is a fundamental statement about the value of poetry as it reflects life itself: essential, vital, and genuine.

Moore’s poem reminds us to appreciate our everyday and experience living more fully. During National Poetry Month 91 years later, the poem continues to startle and even awaken and excite my students. In class, we experiment with language and structure by writing a poem in the style of Moore. The first line is adapted to guide us on topics such as making one’s bed, attending English class, exercising daily, and eating breakfast.

Poetry invites readers to make connections across cultures, experiences, and time. We can become present in a poem as language and form make the poem part of what we experience at this moment, now.

A poem appears and takes a breath with us—from line to line. However, the reader gives the poem full breath and a fuller life with experience. In Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World, Jane Hirshfield explains, “Poetry’s work is not simply the recording of inner and outer perception; it makes by words and music new possibilities of perceiving. […] A work of art is not a piece of fruit lifted from a tree branch: it is a ripening collaboration of artist, receiver, and world” (3–4). Granted, all must be present at the table of poetry for reading and understanding: the creator, reader, and society.

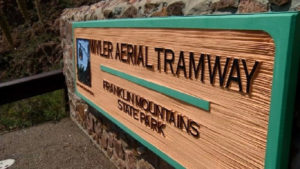

Last year, a colleague and I visited a local mountain range encompassing three states and two countries with a view of 7,000 square miles. Known as the Franklin Mountains State Park, it covers a 24,256-acre patch of the Chihuahuan Desert in the middle of El Paso, Texas.

Ranger Peak – Credit: Lawrence Parent 2009

As we drove from the university campus toward the mountain, nature seemed massive and expansive before us. Wildlife appeared and greeted us, ranging from flowering cacti to birds, deer, insects, and reptiles in movement. When we boarded an aerial cable car to witness the topography and full view at Ranger Peak, 5,632 feet above sea level, another world appeared via all our senses while in motion.

Our eyes awake became our memorable camera as we experienced the vista and natural splendor on earth—as we would experience a poem.

The aerial lift had five spectators: two professors, a father and son, and a park ranger. As we ascended, I imagined what awaited us at the peak. Soon the ranger introduced us to the east side of range, which is part of the Franklin Mountains, and the story behind the mountain, park, and view. Because I wanted a fuller picture, I asked about the earliest inhabitants of the region, but the four-minute ride limited our sharing. As I walked on, I noted that the ranger and historical markers overlook the earliest people who frequented the mountains, the Mansos, and thus their recorded experience is absent.

In contrast, in the following narrative poem I attempt to document the historical presence of the Mansos, who are essential and vital to the story of this natural landscape and view.

Variation on a Theme by Lucille Clifton

on the cable car at Sierra de los Mansos, 2nd May 2015

nobody says the names

the given names by first peoples

to rocks once moved so moved

by the people calling this home

now unidentified and indistinct

instead we only hear of purchases

and treasures galore of land

the ranger remembers with glories

claimed yet he does not know

the names we know of the sacred

rocks and hands once touching earth

some bodies sat here and carved

mountains of lineage with rocks

fed fish and manna on these rocks

how waters once flooded the land

shaping rocks and adobe we behold

before us as we ascend into the sky

and rock bed flowers bloom

we know the rocks must know

their own deserted names

and our ancestral names

even if we misremember

or forget to ask what pages

were rewritten without us

without telling what was

and is native and holy here

somebody manifested another

telling by making one history

after the coming of franklin in 1848

erasing some memories and names

we remember and pronounce

Influenced by the poem “at the cemetery, walnut grove plantation, south carolina, 1989” by Lucille Clifton, the poem serves as a counter narrative and a response to my scenic excursion in nature. The coming of Benjamin Franklin Coons, for whom the mountains are now named, changed local economies, geographies, and names.

In all forms, poetry reminds us to be human and humane. Poetry can transform and fuel our imagination as we gain understanding and reflect on the poem’s conversation alongside our living experience. In the essay “Pintura: Palabra” found in the March 2016 issue of Poetry, Francisco Aragón connects Latino visual artists with poets for the “creation of art-inspired poetry” to advance a dialogue. (587). I found it revealing how poetry and life become essential, vital, and genuine in our everyday through the arts and in our classrooms.

With our students, we can experience the vital and reciprocal relationships that poetry can fuel in our everyday lives. This effect can occur across literary tables with memories, stories, and names we seek, find, and pronounce to make poetry come alive.

R. Joseph Rodríguez is assistant professor of Literacy and English Education at The University of Texas at El Paso, located on the border across from Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, México. His research interests include children’s and young adult literatures, socially responsible biliteracies, and academic writing. Catch him virtually @escribescribe or via email: rjrodriguez6@utep.edu.

Works Cited

Aragón, Francisco. “Pintura: Palabra Introduction.” Poetry 207.6. (March 2016). 587-588. Print.

Hirshfield, Jane. Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World. New York: Knopf, 2015. Print.

Moore, Marianne. Observations: Poems. Ed. Linda Leavell. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2016. Print.

Rodr‘guez, Rodrigo Joseph. “Variation on a Theme by Lucille Clifton.” Unpublished poem. 2016. Print.