This post is written by NCTE member Kim Zarins.

[Disclaimer: I don’t have a PhD in composition studies. My PhD is in English with a focus on medieval literature. Besides teaching college literature courses, I write creatively, and my debut young adult novel comes out in September. I am joining the debate on the five-paragraph essay in response to Kathleen Rowlands’ smart “Slay the Monster” journal article, because I think high school and college teachers can work together and set up our students for success—and the five-paragraph essay is setting them up for a really tough time in college. Students don’t find their voices this way and come to college hating how they sound in writing, particularly in the essay form.

[Disclaimer: I don’t have a PhD in composition studies. My PhD is in English with a focus on medieval literature. Besides teaching college literature courses, I write creatively, and my debut young adult novel comes out in September. I am joining the debate on the five-paragraph essay in response to Kathleen Rowlands’ smart “Slay the Monster” journal article, because I think high school and college teachers can work together and set up our students for success—and the five-paragraph essay is setting them up for a really tough time in college. Students don’t find their voices this way and come to college hating how they sound in writing, particularly in the essay form.

As a high-school survivor of this form and now a teacher occasionally receiving it from students trying their best, I have to say I hate this abomination. I hate it so much, I decided to be naughty and condemn the five-paragraph essay in a five-paragraph essay. Here you go. Enjoy. Or not.]

From the dawn of time, or at least the dawn of the modern high school, the five-paragraph essay has been utilized in high school classrooms. Despite this long tradition, the five-paragraph essay is fatally flawed. It cheapens a student’s thesis, essay flow and structure, and voice.

First, the five-paragraph essay constricts an argument beyond usefulness or interest. In principle it reminds one of a three-partitioned dinner plate. The primary virtue of such dinner plates is that they are conveniently discarded after only one use, much like the essays themselves. The secondary virtue is to keep different foods from touching each other, like the three-body paragraphs. However, when eating from a partitioned plate, a diner might have a bite of burger, then a spoonful of baked beans, then back to the burger, and then the macaroni salad. The palate satisfies its complex needs for texture, taste, choice, and proportion. Not so for the consumers of the five-paragraph essay, who must move through Point 1, then Point 2, and then Point 3. No exceptions. It is arbitrary force-feeding to the point of indigestion. After the body paragraphs, and if readers have not already expired, they may read the Conclusion, which is actually a summary of the Introduction. There is no sense of building one’s argument or of proportion.

Second, critical thinking skills and the organization of the essay’s flow are impaired when a form must be plugged and filled with rows of stunted seeds that will never germinate. If we return to the partitioned-plate analogy, foods are separated, but in food, there is a play in blending flavors, pairing them so that the sum is greater than the individual parts. Also, there is typically dessert. Most people like dessert and anticipate it eagerly. In the five-paragraph essay there is no anticipation, only homogeneity, tedium, and death. Each bite is not food for thought but another dose of the same. It is like Miss Trunchbull in the Roald Dahl novel, forcing the little boy to eat chocolate cake until he bursts—with the exception that no one on this planet would mistake the five-paragraph essay for chocolate cake. I only reference the scene’s reluctant, miserable consumption past all joy or desire.

Third, the five-paragraph form flattens a writer’s voice more than a bully’s fist flattens an otherwise perky, loveable face. Even the most gifted writer cannot sound witty in a five-paragraph essay, which makes one wonder why experts assign novice writers this task. High school students suffer to learn this form, only to be sternly reprimanded by college professors who insist that writers actually say something. Confidence is shattered, and students can’t articulate a position, having only the training of the five-paragraph essay dulling their critical reasoning skills. Moreover, unlike Midas whose touch turns everything to gold, everything the five-paragraph essay touches turns to lead. A five-paragraph essay is like a string of beads with no differentiation, such as a factory, rather than an individual, might produce. No matter how wondrous the material, the writer of a five-paragraph essay will sound reductive, dry, and unimaginative. Reading over their own work, these writers will wonder why they ever bothered with the written word to begin with, when they sound so inhuman. A human’s voice is not slotted into bins of seven to eleven sentences apiece. A human voice meanders—but meaning guides the meandering. Voice leans and wends and backtracks. It does not scoop blobs of foodstuff in endless rows. If Oliver Twist were confronted with such blobs of written porridge, he would not ask for more.

In conclusion, the five-paragraph essay is an effective way to remove all color and joy from this earth. It would be better to eat a flavorless dinner from a partitioned plate than to read or write a five-paragraph essay. It would be better to cut one’s toenails, because at least the repetitive task of clipping toenails results in feet more comfortably suited to sneakers, allowing for greater movement in this world. The five-paragraph essay, by contrast, cuts all mirth and merit and motion from ideas until there is nothing to stand upon at all, leaving reader and writer alike flat on their faces. Such an essay form is the very three-partitioned tombstone of human reason and imagination.

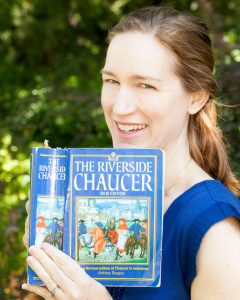

Kim Zarins is a medievalist and an Associate Professor of English at the California State University at Sacramento. Her debut young adult novel, Sometimes We Tell the Truth, retells Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales with modern American teens traveling to Washington D.C. Find her on Twitter @KimZarins.