From the NCTE Standing Committee on Literacy Assessment

This post was written by NCTE member Bobbie Kabuto, the chair of the NCTE Standing Committee on Literacy Assessment.

As many of us start to prepare for and aim for more normalcy in our fall teaching, we will also be provided with results from a variety of standardized assessments. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is also known as “the Nation’s Report Card.” NAEP has reported on students’ academic performances since 1969. Unlike standardized assessments conducted through individual states, NAEP provides a uniform and national overview of students’ academic performances. As a result, NAEP reports play critical roles in framing conversations around assessment in a variety of subject areas, including reading and writing.

On April 27, 2021, NAEP released its report The 2018 Oral Reading Fluency Study, which is the first study of oral reading fluency from NAEP since 2002. The NAEP report aimed to assess the oral reading fluency of fourth-grade students by asking students to read four short passages aloud. The Executive Summary (p. iii) highlights the common decontextualized manner by which oral reading is conducted: “Also, to understand the likely underlying sources of poor fluency—inefficient word recognition and phonological decoding—students were timed and scored for accuracy as they read lists of words and pseudowords (e.g., jad). Pseudowords were used to demonstrate students’ ability to phonologically decode unfamiliar words.”

The NAEP report outlines five key findings that fall into two main areas:

- reading as defined through accurate word reading measured through decontextualized word and pseudoword reading, and

- the underperformance of students of students of color so that “51 percent of Black, and 46 percent of Hispanic fourth-graders fell into the below NAEP Basic group. Black students were also overrepresented in the below NAEP Basic Low subgroup.”

In my reading, I found that the report does the following:

- It assesses reading in artificial and unnatural ways. Students are assessed with headphones behind cardboard carrels so they cannot hear others around them, but they also cannot hear themselves, which normally helps them to self-monitor how they sound when they read. (The use of pseudowords reminded me of a student who once asked me why they needed to use “fake words” when there were so many “real words” they needed to learn.)

- It situates reading research through a White, middle-class, English-dominant perspective that negatively impacts students of color and multilingual students. The report findings compare and rank students to “typical” students without telling us who these “typical” students are.

- It perpetuates inequalities by ignoring the complex social contexts and ways of constructing meaning that define reading and what it means to be a reader. Every finding ranks and sorts so that students of color (Black and Hispanic) underperformed in every aspect of the assessment when compared to White students.

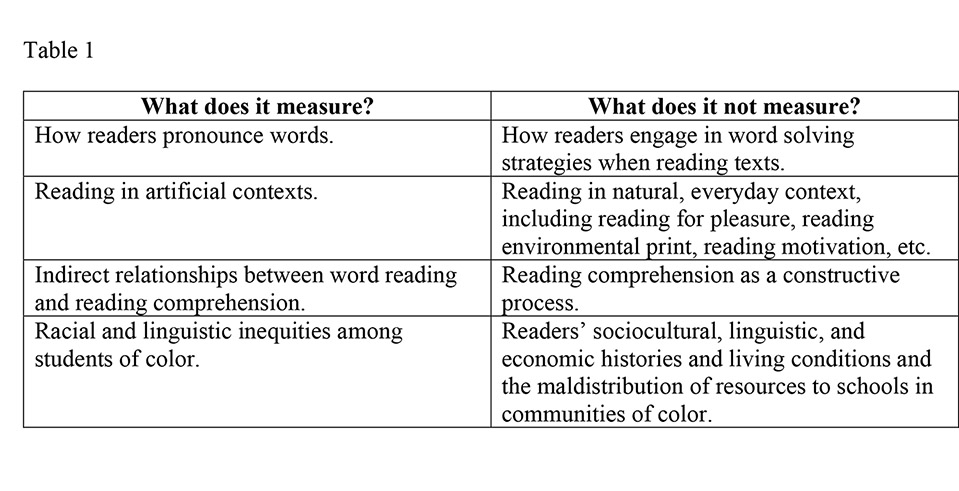

Through page after page, I wondered how we—teachers, scholars, advocates, and school leaders—can make sense of reports such as the NAEP report to understand what they measure and do not measure.

In Table 1 below, I outline a few concepts that immediately came to mind.

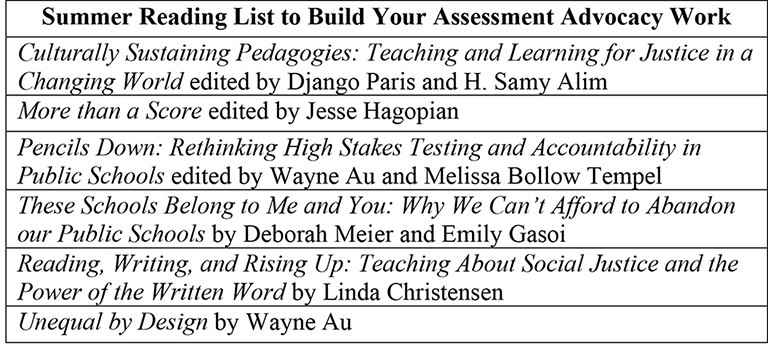

In trying to make sense of the NAEP findings, I am reminded of Eric Turley’s blog post Everyday Advocacy and Literacy Assessment in which he asks four critical questions on how to make sense of assessment practices and how they inform the conservation around student learning.

Chris Hass’ blog post Putting Advocacy on the Ballot in November reminds us of the toxic culture of and the narrowing of curriculum due to standardized and high-stakes testing that started in 2002 under the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act and that continues under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

We will see more and more reference to the findings in The 2018 Oral Reading Fluency Study in the upcoming months in a variety of local, state, and national media venues, framing arguments on how fourth-grade readers are falling below grade level standards and how students of color underperform in reading.

With this, the advocacy work from school leaders becomes of critical importance so that we don’t fall into yet another trap that promotes and increases the needless amount of testing in schools. As we emerge from the pandemic, we should take this time to reflect on what we learned about our students when standardized assessments were halted, to consider how we can use assessments to advocate for what students know.

Bobbie Kabuto is professor and department chair of the Elementary and Early Childhood Education Department at Queens College, City University of New York.

Bobbie Kabuto is professor and department chair of the Elementary and Early Childhood Education Department at Queens College, City University of New York.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.